The critic Sainte-Beuve was so concerned about the rise of popular books and their potential to corrupt, that in 1839 he denounced them all as ‘industrial literature’, in other words, mass produced works that showed no regard for artistic or moral quality. A few years later another critic, Alfred Nettement (such a good name it feels as though it ought to be a pseudonym: ‘Alfred Neatly’), specifically attacked the serial novel (made possible by the commercialisation of the press, lower subscription fees and advertising) for contributing to contemporary ‘literary disorder’. And not just that: serial novels’ depravity, addictive qualities, and lack of beauty were hastening the decline of civilisation, he maintained; society was going to be ‘flooded by its sewers’ and trashy novels would be bobbing along on that tide.

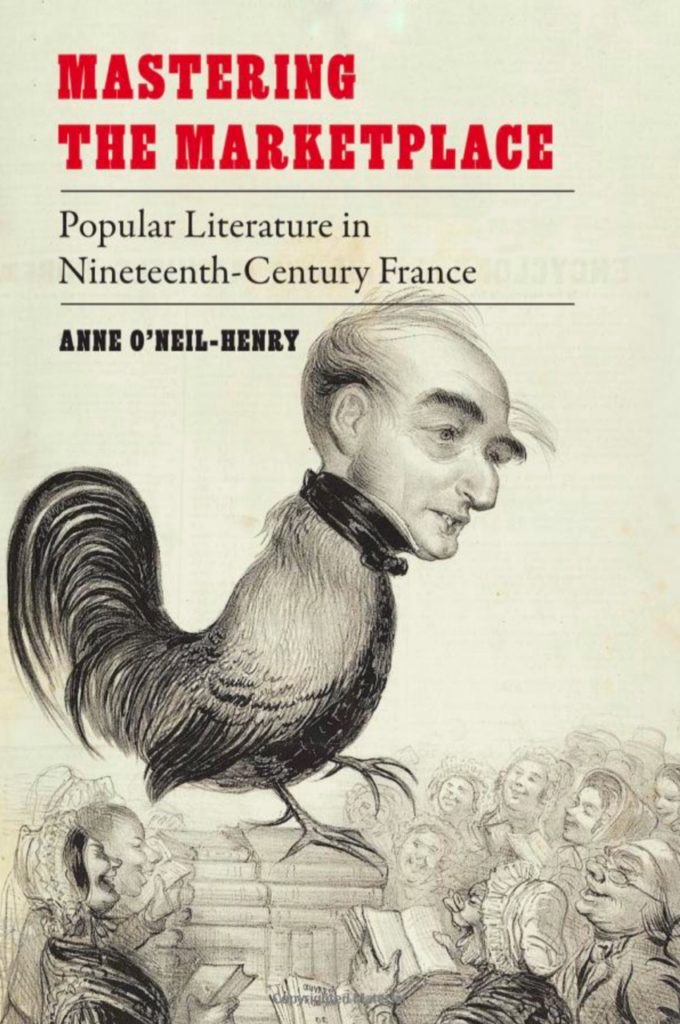

The kind of literature that gave these critics the horrors was written by two of the writers Anne looks at in her book, Mastering the Marketplace: the now largely forgotten Paul de Kock, who had a lucrative career as a popular novelist that lasted half a century despite being scorned by many of his fellow writers, and Eugène Sue, whose Mysteries of Paris was an international publishing sensation in the 1840s but has been described as ‘the most important work of nineteenth-century French fiction that is virtually unread in English’.

In our conversation we talk about the rise of the man of letters (and they were all men, alas), genre-switching authors and the small print-runs of big names. Anne’s dog also puts in a brief appearance, but doesn’t stick around.