![]() This week’s podcast is a conversation with Griselda Pollock about her recent book, Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory. Griselda Pollock is Professor of Social and Critical Histories of Art at the University of Leeds and has for forty years been challenging the way in which art is studied in isolation from other forms of visual culture, and, especially, the ways in which the role of women artists has been marginalized.

This week’s podcast is a conversation with Griselda Pollock about her recent book, Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory. Griselda Pollock is Professor of Social and Critical Histories of Art at the University of Leeds and has for forty years been challenging the way in which art is studied in isolation from other forms of visual culture, and, especially, the ways in which the role of women artists has been marginalized.

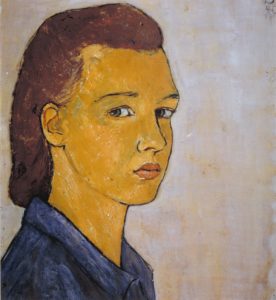

Charlotte Salomon, the German-Jewish artist, whose intense, powerful work Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?) was unknown for decades after her death, may be the perfect subject for Pollock: in the interview she describes how her new book represents a culmination of themes she has pursued throughout her career. It was also an unusually difficult book to write; two earlier drafts were set aside before being published in this third incarnation.

Charlotte Salomon was born Berlin in 1917. Her mother committed suicide when Charlotte was eight. She trained in illustration at the art academy in Berlin, one of a tiny number of Jewish students admitted. She specialized in illustrating Märchen, German fairy tales and folk tales.

Charlotte Salomon was born Berlin in 1917. Her mother committed suicide when Charlotte was eight. She trained in illustration at the art academy in Berlin, one of a tiny number of Jewish students admitted. She specialized in illustrating Märchen, German fairy tales and folk tales.

In 1938 she fled Germany alone and joined her grandparents in exile in the south of France. There her grandmother jumped to her death from a window in 1940, the same year Salomon and her grandfather were interned by the French authorities in a concentration camp in the Pyrenees.

In the chaotic conditions after the German invasion of France, they were released from the camp and in hiding between late 1940 and early 1942 Charlotte Salomon made the huge, complex, multi-layered artwork that is Leben? oder Theater? – Life? or Theatre? – in an extraordinary burst of sustained creative activity. In 1943 Salomon was rearrested and deported to Auschwitz, where she murdered on 10 October five months pregnant and aged 26.

Life? or Theatre? is a single work comprising nearly 800 paintings, 330 of them with transparent overlays, carrying dialogue or commentary that often play with the visual image of words. They also suggest melodies for the scenes. ‘Something wildly unusual’ Salomon herself called the work. Griselda Pollock characterizes it as ‘Challenging, enigmatic and demanding’. Life? or theatre? was never exhibited or even seen by anyone during Salomon’s lifetime. In early 1943 Salomon had wrapped her paintings in large packages and handed them over for safekeeping, reportedly saying, ‘This is my whole life.’ The work came into her father and stepmother’s possession in 1947, but it was not exhibited until 1961 in Amsterdam.

Griselda Pollock, University of Leeds, December 2017

Art historical interest grew from the 1990s; there was a big show in London in 1998 at the Royal Academy, which later travelled to North America. In recent years Salomon’s work has inspired artists, playwrights, filmmakers, opera composers, dancers, poets, performance artists, novelists, as well as historians, literary scholars, feminist scholars, scholars of Jewish studies, life narratives, autobiography, and Holocaust studies.

Griselda Pollock is critical of the impulse to reduce Salomon’s work to autobiography or use her life story as inspiration for other works of art. Here’s a short extract from our conversation. Click on the links above or below to listen to the full interview:

Griselda Pollock

What these appropriations do is appropriate out of her work the historical person Charlotte Salomon. Now we know Charlotte Salomon was probably very depressed, very quiet, very mousy, very withdrawn. Alfred Wolfsohn (1) said she was the least responsive of any of the people he worked with trying to bring them out of themselves. And then we get this work which is so sharp, so full of sardonic humour, so cruel in its reading of the complicity and compromises and indeed crimes of adults. You can’t match the two by turning Leben? Oder Theater? into a source for a biographical film.

But what happens is people identify with Charlotte Salomon – the extreme form is David Foenkinos, this French author who thinks she is his ‘other self’ (2) – to continuous stories of playwrights, of dramatists, and they turn it into a story deriving their mise-en-scène from the paintings and thus erasing the central fact: she chose to paint. She chose to compose on a flat surface using colours; she says ‘there was the sun, a paint brush, palette, and you’ (that’s the person she’s addressing this work to). And that’s the point. We miss, we lose that. So I feel that it’s inevitable that the extraordinariness of this young woman’s life and death pierces us and we should be pierced by it, but not to the extent that we then appropriate her as our own avatar.

But what happens is people identify with Charlotte Salomon – the extreme form is David Foenkinos, this French author who thinks she is his ‘other self’ (2) – to continuous stories of playwrights, of dramatists, and they turn it into a story deriving their mise-en-scène from the paintings and thus erasing the central fact: she chose to paint. She chose to compose on a flat surface using colours; she says ‘there was the sun, a paint brush, palette, and you’ (that’s the person she’s addressing this work to). And that’s the point. We miss, we lose that. So I feel that it’s inevitable that the extraordinariness of this young woman’s life and death pierces us and we should be pierced by it, but not to the extent that we then appropriate her as our own avatar.

So in all of the things that people make – ballets, to theatres, to plays –they project themselves into her, and my position is she is radically unknowable to me and, rather like Jacqueline Rose, I’ve argued she doesn’t have to be an ideal, or nice, or lovable, or bearable person. She has to be an honest one. And that’s what I think the work is about: what is authenticity? How is it to face both the complexity and compromised nature of the world in which we live and then the horror of its politics and to know that you yourself are compromised? So much of these stories I think end up with ballets, dances, plays which either overemphasize the tragedy – they all end with her death -–but Leben? Oder Theater? didn’t end with her death, it ended with her saying ‘I choose not to die’. And the fact that she was murdered is the historical catastrophe we have to witness, but we can’t collapse it with her as an artist.

(1) Alfred Wolfsohn (1896–1962) was born into a progressive Jewish family and educated in Berlin. He studied law at university but was musical, playing the piano, viola and violin as well being trained in singing. He was conscripted in 1914 and served on the French and Russian fronts. Discharged in 1919 suffering from the effects of mustard-gas poisoning and shell shock, he endured intense physical and psychological symptoms for the next ten years. He had also lost his voice. In his journey back to mental health, memory and a voice, Wolfsohn discovered a therapeutic relation between voice and psyche, between voice and body, between Eros, Thanatos and creative individuality, that has become the basis for a teaching philosophy still practised by individuals and a company that carries on his legacy.

(2) Foenkinos’ novel Charlotte won praise and prizes, and has been translated into English and German. Not all critics agreed though; David Caviglioli’s stinging review in L’Obs suggests Foenkinos’ travels in Salomon’s footsteps are no more profound and enlightening than a Beatles fan’s pilgrimage to Abbey Road. ‘He’s invented the tourist novel,’ Caviglioli writes.