This programme from the archive features a conversation I had back in 2010 with Robert Irwin about the extraordinary world of the camel. Robert is a true polymath: Arabist, historian, translator, novelist, publisher, anthologist. His book on the camel in Reaktion Books Animal series draws on his deep knowledge of Middle Eastern history and culture, but it also extends far beyond. For example, it delves into the camel’s prehistory, as you’ll hear in the interview, and also presents a huge variety of camel history and lore from all over the world.

This programme from the archive features a conversation I had back in 2010 with Robert Irwin about the extraordinary world of the camel. Robert is a true polymath: Arabist, historian, translator, novelist, publisher, anthologist. His book on the camel in Reaktion Books Animal series draws on his deep knowledge of Middle Eastern history and culture, but it also extends far beyond. For example, it delves into the camel’s prehistory, as you’ll hear in the interview, and also presents a huge variety of camel history and lore from all over the world.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation, which you can listen to by clicking on the links above or below.

Presumably your interest in the camel grew out of your interest in the Middle East and its history, politics and culture?

Robert Irwin

Yes, I think the book was originally going to write was devoted solely to the camel’s role in history and what a large part it played in the spread of Islam and the rise of the Arab empires. The book I eventually wrote is much broader and deals with the camel in the United States and Australia and China. It deals with literary and cinematic and artistic aspects. Everything is there. and a lot about the physiology and evolution of the camel.

Hedgehog & Fox

And I got the overall impression you felt the camel had been a bit maligned. I mean, obviously in the Middle Eastern culture it’s got a prized place, but particularly in Western culture, it’s not had an especially good press, has it?

Robert Irwin

I think in the Middle Ages the camel was OK. The people who wrote about the camel or painted it didn’t really have a clue, so sometimes they made it an emblem of lust and sometimes they made it an emblem of chastity and faithfulness. It was all over the place in the medieval period.

But in the 19th century empire builders and explorers without much experience such as Charles Doughty really had it in for the camel, and Kipling is one of the best examples of somebody who again and again gets his knife out for the camel. Not just that famous story How the camel got its hump, but also quite a lot of poetry attacking the camel.

In the 20th century it had some defenders. TE Lawrence notably, very well-informed and sensitive to the abilities and charms of the camel. Wilfred Thesiger, another. And quite a lot of Australians have taken to the camel and written in its defence, even though of course in Australia today the feral camel is officially classified as vermin and is regularly hunted down and culled.

Hedgehog & Fox

Now let me ask you about your own personal encounters with camels. How far back do you go with camels?

Robert Irwin

It must be about twenty-five years or more when I took my daughter for a ride on the Bactrian camel in Regent’s Park Zoo. These days you can’t do that, it’s politically incorrect to ride these animals and you cant pay 50p for a camel right. But then as I started to research the book became reluctantly aware I would have to ride a camel.

And so I think the first camels I rode were in Rajistan; there are surprising number of camels in northern India. They really are used for heavy labour. It’s not just a tourist thing and they’re also used for meat of course as well. And subsequently I’ve ridden a camel or two in Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Hedgehog & Fox

And what is it like being up close to them?

Robert Irwin

It’s frankly frightening, because of the way a camel can kick quite unexpectedly in any direction; its legs are extraordinary. Also you’re even more likely to get spat at and then there’s its bad breath, that’s a bit off-putting. The breath depends on what it’s been eating but generally camels have bad breath. And then to sit on a camel and then its back legs go up and you’re pitched forward and then suddenly the front legs go up – it’s terrifying and equally terrifying coming down. I guess one gets used to it of course.

Hedgehog & Fox

You mentioned the fact that you went back into the prehistory of the camel. Tell me a little bit about the camel’s ancestors, because you’ve got some mega prehistoric camels pictured in the book.

Robert Irwin

Yes, very difficult to get pictures of prehistoric camels from anywhere. I had a real hunt. But yes, the camel actually starts out in what is now the United States in the Eocene period, though scientists can’t agree within the nearest hundred million years when apparently. The first camels were no taller than hares – extraordinary – but then there’s a proliferation of different types of camel, all of which are extinct now, many of which were giants. They were very tall, had very long necks and they obviously fed off the canopy of forests and they roamed across what was then savannahs of America. A

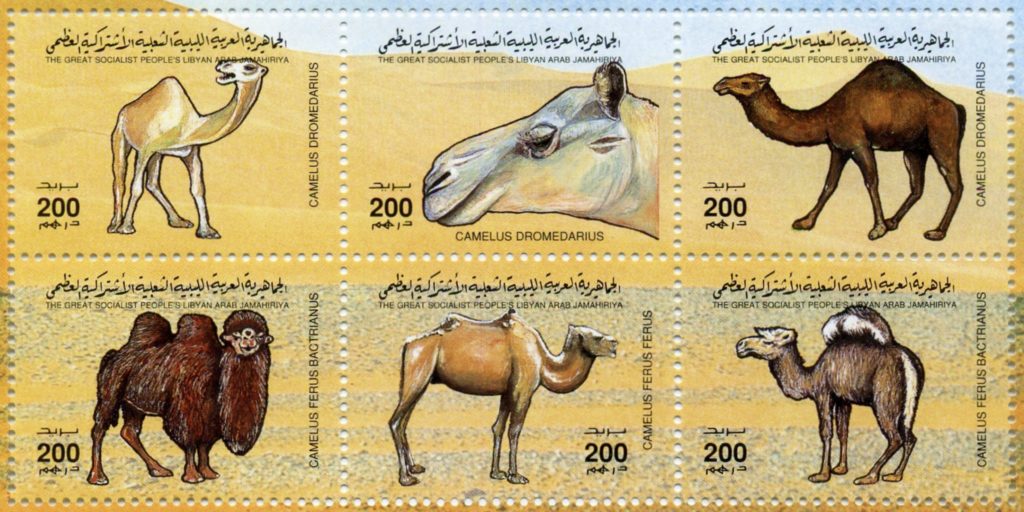

Most of them died out and we get left with what is recognisably the camel today, which emigrated from North America and it went in two directions: a lot of the camels went south and over the process of millions years turned themselves into llamas, vicunas and alpacas and guanocos, I think. Whereas other camels crossed the Bering Strait at the time when there was a land bridge into Asia and became the Bactrian and the dromedary. And these were of course quite large camels, but nothing like the size of the prehistoric camels.

Quite recently in Syria, I think it was in the last four or five years, they found the remains of a giant dromedary, which is interesting and it seems to have been killed by fairly primitive Stone Age people. But hitherto it hadn’t been known that any giant camels had got across onto the Eurasian landmass.

Hedgehog & Fox

And you say there is domestication and domestication when it comes to camels. Tell me a bit about that. When did that happen as far as we can tell?

Robert Irwin

Well you can’t. Flatly the evidence isn’t there, that’s for starters. You can find camel remains in prehistoric sites, but that doesn’t mean you’ve got a domesticated camel. It just means somebody’s got lucky and killed a camel or found one dead anyway. Also, it’s not one lot of domestication. It’s domesticated in South Arabia at a different time from North Arabia, and that’s a very different date of domestication from domestication in China and Mongolia, which anyway is a different species to the the Bactrian camel.

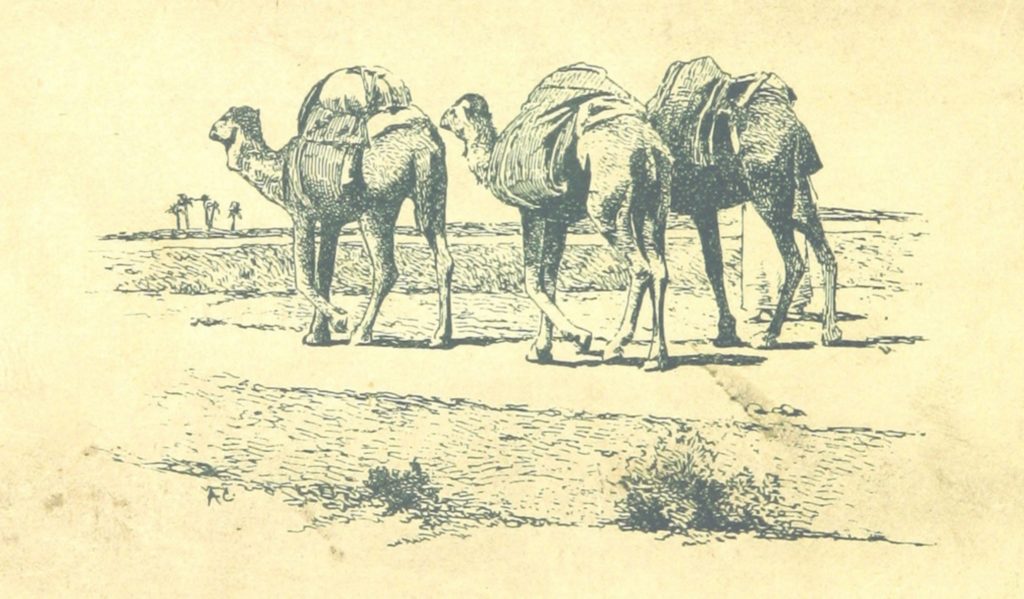

And then there’s the question of what you mean by domestication. Probably the first camels were just kept in a herd and you got the milk and you got the meat and when the beast died you got the hide. It’s a later development that they’re used for transport, transporting goods and for riding. And later yet, with sort of what seems a very simple development of a certain type of saddle, they become seriously useful for warfare. And that’s probably part of the broad background to the rise of Islam, the development of the North Arabian saddle.

Hedgehog & Fox

I loved that you cited the fact that in Arabic there’s a verb which means ‘to get off your camel and get onto your horse’. And that was presumably in the process of warfare, you used the camel for the long-distance transport, but then when you went in to attack that was the horse’s job?

Robert Irwin

In general, yes, the horse is faster and more useful on the battlefield. And I think perhaps a little easier to control. So they fought for preference on horseback, having used the camel to get there. Rather similar to the camel corps that formed in the late 19th, early 20th centuries in Britain and France and elsewhere. The general practice was to ride your camel to the place where you were going to fight and then dismount. Camels are too big a target. The camel gets startled by all the gunfire if it’s right next to it. So in general one rode the camel to the battlefield and then dismounted and fought on foot.

Hedgehog & Fox

But your major point, from which I slightly deflected you there, is that the camel can be seen as a major vector for the transmission or the spread of Islam.

Robert Irwin

Yes, and I benefited greatly from an article that was published a few years ago in the Bulletin of the school of Oriental and African Studies by Patricia Crone, where she suggests that Mecca and Medina in the seventh century were not really trading in spices as an older generation of scholars used to think.

The seventh century we’re talking about the century in which Mohammed begins to preach and the Arabs begin to fan out their armies from the Arab peninsula. In the early seventh century and in the century before there was a lot of warfare taking place between the Romans and the Persians. And though it’s not obvious to a modern person warfare in this period ate up leather like Modern Warfare eats up oil. the Roman army needed leather for its armour, for its tents, for its baggage, for saddles, for everything.

And where are they going to get that? Obviously they’re going to go mostly for local providers and this is where the Bedouin of the Hejaz come in with their camels. So they’re trading in camel hide with the Romans, probably also with the Persians, and that has two consequences. First, it makes them somewhat prosperous and secondly it makes them very familiar with how the Roman and Persian armies operate and makes them aware of where their weaknesses are, probably also encourages Arabs to move out of the peninsula into Syria and Iraq, even ahead of the Islamic conquests.

Hedgehog & Fox

Your book is very richly illustrated in colour and I wondered when the camel becomes a creature with an iconography?

Robert Irwin

I can’t pronounce authoritatively on that, but I would think that among the earliest representations of the camel are the ones you find in China: the ceramic camels that were customarily left in wealthy men’s tombs. The camel would be part of the tomb apparatus, as it were, because it’s carrying a load of wealth; it means that when the dead man comes into the next life there is a load of wealth being carried by this incarnation, reincarnation, of the ceramic camel. There are lots and lots of these ceramic camels. Every major museum in this country has at least one specimen.

Hedgehog & Fox

And you mentioned earlier that the medieval European mind was a bit ambivalent about what value to ascribe to the camel. Is that something which you find as you go round the camel world, that there are different attributes selected and highlighted in the way camels are portrayed in the iconography?

Robert Irwin

Yes, the most striking example is Japan, where the Japanese for camel – I hope I pronounce it right – is ‘rakuda’, and that really means pretty much the same as sexual enjoyment. So the camel becomes a symbol of connubial bliss; not something that had occurred to many people in the West. The other thing about the camel in Japan is of course until the Dutch paraded one round Japan in the seventeenth century, they’d never seen a camel. I think all their artists and writers took it for granted it was a mythological beast, just like a unicorn and gryphon. So it was a bit of a shock when it actually arrived with the Dutch East India Company.

Hedgehog & Fox

Your allusion to the sex life of camels reminds me that was something else you investigated in this book!

Robert Irwin

Oh yes, it was pretty disgusting really. Yes, I think the camel urinates backwards, the male camel. I’ve forgotten the word for it but it, as it were, inseminates, screws forward. The other thing about it is that when it’s on the rut, it splashes and sprays water all over the place. The female urinates like mad too. It’s a sort of conspicuous consumption, you know, using all this water to show how much desire you have or what a healthy water-filled beast you are. The odd thing was, so many people I read or had conversations with believe the camel cannot have sex without human assistance. This is obviously not true, as we wouldn’t have feral camels all over Australia and elsewhere in the world…

Hedgehog & Fox

What is the position of the camel in the world today? You write about how some Arab nations have rather distanced themselves from the camel, which they see as part of their past but not necessarily part of their future. So how do you rate the camel’s prospects?

Robert Irwin

Sorry to give such a complex and oblique answer, but there is no one single position. It’s true that the use of the camel has declined drastically in countries like Iraq, Syria, Lebanon. Camel herding’s almost vanished. On the other hand in the United Arab Emirates, and I think in Oman and other territories in the Gulf region, Saudi Arabia – There’s quite a cult of the camel and there are wealthy men who keep prestige herds and there’s camel racing and camel beauty contests and the camel is very much part of almost an artificially revived Arab culture there. There is a lot of money being spent on camel research in the peninsula. but still not vast numbers.

Most dromedaries are found not in the Arab world but in North East African, countries like Kenya and so on, where they’re doing okay and there are a lot of international bodies pressing east Africans to take up camel herding rather than goats or cattle. It’s ecologically much more satisfying, economically it’d be beneficial. And then you’ve got herds of feral camels in Australia, camels that had been used as pack beasts before the coming of railway and the lorry, and they’ve been let loose in the desert and they’ve multiplied to a nightmarish extent and they’re quite a problem.

Then you’ve got a fairly flourishing domesticated population of Bactrian camels in China and Mongolia mostly and they’re fine. But there’s yet another, effectively another species of Bactrian camel, they’re the wild Bactrian and that exists only in certain rather remote areas of the desert crossing the frontier between China and Mongolia. And it’s a seriously threatened species. There are hunters and there are mining prospectors and others out to kill them. Also there are wolves.

The wild Bactrian is under more threat than the panda, it’s one of the most seriously threatened species. It is a different species and has all sorts of different physical characteristics and it also has a different DNA. People should get in touch with John Hare’s Wild Camel Protection Foundation and help him protect these wild camels. They’re really interesting beasts.

Hedgehog & Fox

So it’s really a mixed picture for the camel…

Robert Irwin

Absolutely, very mixed. The feral camels in Australia are going from leaps to bounds and these other ones are practically extinct.